Dietitian Chloe Hall looks at what Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (PoTS) is, what causes it and how dietitians can help to treat it.

Since the pandemic, I have been supporting an increasing number of patients who have developed PoTS, along with gastrointestinal side effects. The incidence of this condition is not well documented, however prior to the pandemic it had been estimated that 0.2% of the population was affected by this condition, however no study has looked at the UK population specifically and the condition is often underdiagnosed1.

In practice, dietitians are seeing an increase in the number of patients seeking support for PoTS and this is potentially related to the increased prevalence as a result of COVID-192. One of the difficulties in establishing how common the condition is is the lack of universally accepted diagnostic criteria and in many areas a lack of a robust diagnostic and care pathway3.

Unfortunately obtaining a diagnosis is often not straightforward and patients often struggle with symptoms for a long time, leading to understandable frustration. By familiarising ourselves with the condition, and the evidence-based dietary advice that may help to alleviate some of the symptoms, we can ensure that any further delay in treatment is avoided. In this article, I’ll be discussing the symptoms of PoTS, what dietary advice we can give to reduce some of these and other dietary issues that those with the condition may present with.

What is PoTS?

PoTS is a type of dysautonomia; a complex disorder of the autonomic nervous system, the system that regulates involuntary physiological processes4, 5.

It is defined by the Heart Rhythm Society as a ‘collection of symptoms present for at least six months associated with cardiovascular abnormalities on standing, where the heart rate increases inappropriately and remains persistently raised without significant orthostatic hypotension’1.

In view of this, symptoms can often occur on moving from sitting to standing or standing for a period of time and can often be relieved by lying flat.

What symptoms may someone with PoTS experience?

The symptoms that those with PoTS may experience can be wide-ranging and not limited to the cardiovascular system. These may include orthostatic, non-orthostatic and general symptoms6, 7. The most common symptoms are detailed below:

- Orthostatic symptoms: Dizziness/lightheadedness, pre-syncope or syncope, palpitations, shortness of breath, tremor, weakness and chest pain.

- Non-orthostatic symptoms: Gastrointestinal symptoms including bloating, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhoea and bladder problems.

- General symptoms: Fatigue, sleep disturbance, migraines, brain fog, muscle weakness, skin flushing, myofascial pain.

Some people with PoTS can be so significantly affected by the condition that it can leave them bedbound or needing to use a wheelchair8.

What causes PoTS?

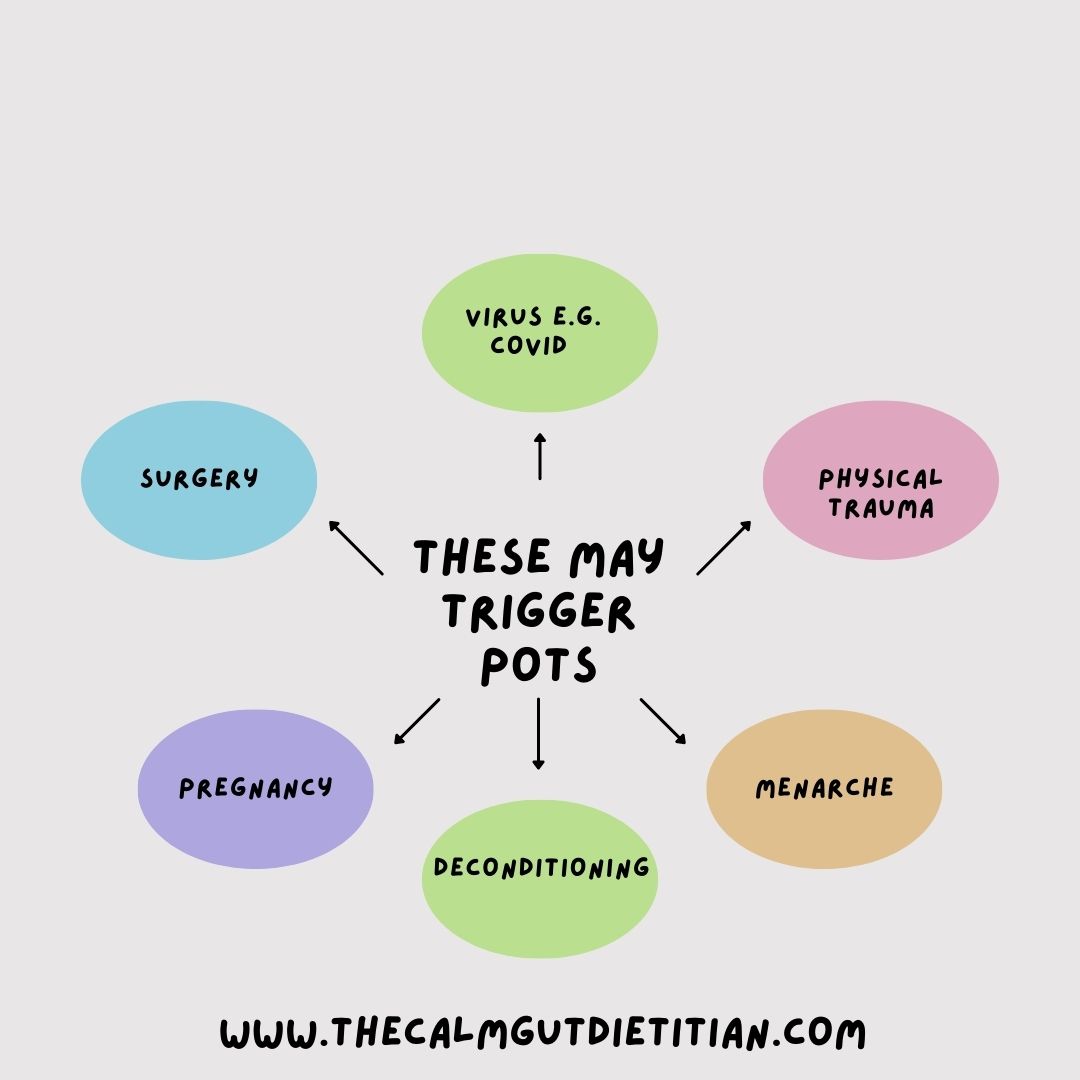

It is not completely clear what causes PoTS, however in a number of cases it is preceded by physical or immunological stress9, 10. Some of the proposed triggers are detailed below.

What is the treatment of PoTS?

There is not one single treatment that is universally effective and response can be very individual1. Before medication is started, non-pharmacological treatments such as diet and fluids, compression garments and exercise should be trialled1. If these do not bring adequate symptom relief then various medications may be used such as:

- Those that slow down the heart rate such as Ivabradine or Beta blockers.

- Those that narrow blood vessels to help return the blood back to the heart such as Midodrine.

- Those that increase blood volume such as Fludrocortisone or Desmopressin.

There are, also, other medications that may be used on an individual basis.

How can a dietitian support with symptom management in PoTS?

It has been suggested that a nutritional assessment should be offered to all those with PoTS11. Not only can dietary changes and fluids help orthostatic symptoms but dietetic support for those with gastrointestinal symptoms is vital to ensure that someone is able to get the nutrients they need whilst minimising symptoms.

It is important that eating disorders are screened for as studies have found that there is a higher incidence of these amongst adolescents with PoTS12.

Further studies are needed to clarify whether this is, also, true of the adult population, however screening for this in patients of all ages seems sensible given the difficult gastrointestinal symptoms many of those with PoTS experience. These symptoms in themselves may increase the risk of developing an eating disorder13.

In addition to this, if patients are presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms a coeliac screen should be offered, as the risk of coeliac disease may be four times higher in those with PoTS than in those without the condition14. Other key considerations when assessing patients with PoTS, as well as the standard things included in a Dietetic assessment, are any other environmental or physical factors that may affect their symptoms and dietary intake. Non dietary triggers for an exacerbation of PoTS symptoms are shown below.

As previously discussed it is important that diet and fluid are looked at as first line strategies prior to any trial of medications.

First line advice that may help minimize PoTS symptoms include:

- Aiming for 2-3 litres of fluid a day1, 15.

- Aiming for a salt intake between 10-12g daily1.

- Small frequent meals16.

- Reducing refined carbohydrates17.

- Avoiding or reducing alcohol intake16.

- Avoiding caffeine containing energy drinks16.

The aim of increasing fluid and salt intake is to increase blood volume resulting in reduced symptoms, as those with PoTS are thought to have a 13% reduction in blood volume compared to healthy controls18, 19.

Increasing fluid and salt intake may be challenging, especially for patients that have a reduced intake of food as a result of the, sometimes, debilitating symptoms.

Dietetic support is key to help support patients to do this in a way that is practical for them. Salt tablets are sometimes prescribed by specialist medical teams or electrolyte tablets are available over the counter if patients are struggling to get enough salt through their diet alone.

What other nutritional symptoms may those with PoTS present with?

Those with PoTS experience a range of comorbidities at a higher rate than the general population and these comorbidities can affect their nutritional status further2. These comorbidities include:

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

- Mast Cell Activation Disorder (MCAS)

- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic fatigue Syndrome (CFS)

- Fibromyalgia

- Gastroparesis

As dietitians we are well placed to help support patients with a complex medical history and multiple symptoms, in order to ensure that they are able to have a healthy balanced diet, maintain their weight and enjoy food again. Those with co-existing conditions may follow a range of diets, such as the low histamine diet or the low FODMAP diet, which may impact on their nutritional intake further so dietetic support is particulary important if following any of these.

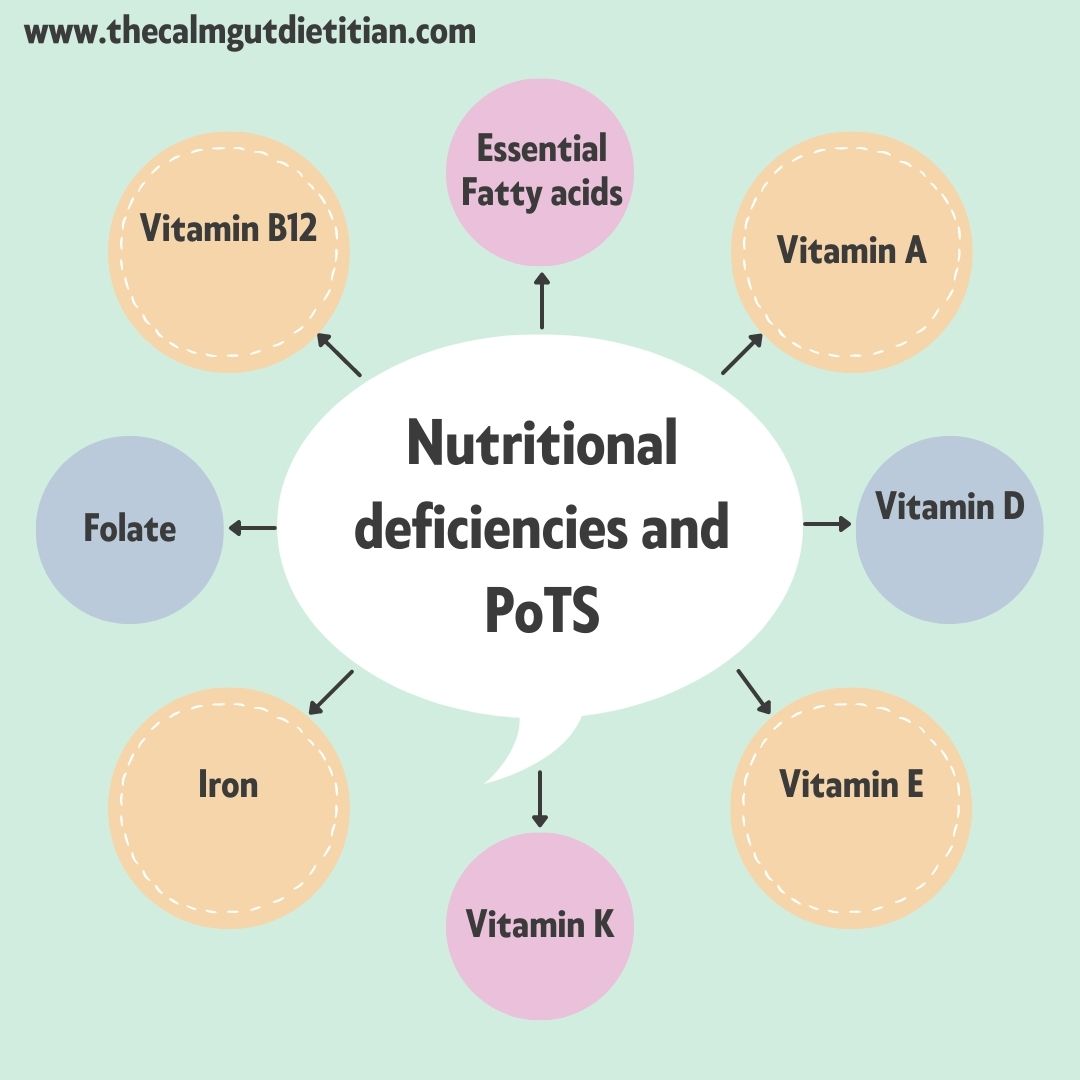

As up to 90% of those with PoTS have gut symptoms, nutrient deficiencies can occur due to a combination of restrictive diets due to very challenging symptoms, and malabsorption11. Correction of these deficiencies should be a priority, as for some patients the correction of these may improve some of their orthostatic symptoms20. The image shows some of the nutritional deficiencies that can occur due to this condition.

Unintentional weight loss and struggling to maintain a healthy body weight can be common due to the high incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms, food intolerances and co-existing conditions. In addition to this, symptoms may make preparing and cooking food extremely challenging without support and, therefore, practical dietary advice is essential. First line nutrition support should include the use of oral nutritional supplements if required, however often standard first line sip feeds may not be tolerated depending on the co-morbidities and gastrointestinal symptoms11. Based on current research it isn’t clear how many patients need enteral feeding, however those that are more likely to require non oral feeding include those with a lower BMI, have gastrointestinal symptoms and delayed gastric emptying21.

Conclusion

It has become increasingly important with the growing incidence of PoTS post covid that dietitians recognise the symptoms of PoTS. By identifying those patients that we suspect may have developed dysautonomia we can ensure to flag this to a patient’s medical team so that investigations for this can be done, if deemed appropriate, and patients get the support that they need in a timely manner.

Due to the wide-ranging symptoms, the management of PoTS needs a multi-disciplinary (MDT) approach, combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures, and dietitians are an important part of that MDT22. It can be an extremely challenging condition to manage and live with and the symptoms can be variable and impact on our patients quality of life so support is vital23.

References

- Sheldon RS, Grubb BP, 2nd, Olshansky B, Shen WK, Calkins H, Brignole M, et al. 2015 heart rhythm society expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of postural tachycardia syndrome, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, and vasovagal syncope. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12(6):e41-63.

- Harris CI. COVID-19 Increases the Prevalence of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: What Nutrition and Dietetics Practitioners Need to Know. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(9):1600-5.

- Olshansky B, Cannom D, Fedorowski A, Stewart J, Gibbons C, Sutton R, et al. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): A critical assessment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(3):263-70.

- Vernino S, Bourne KM, Stiles LE, Grubb BP, Fedorowski A, Stewart JM, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): State of the science and clinical care from a 2019 National Institutes of Health Expert Consensus Meeting - Part 1. Auton Neurosci. 2021;235:102828.

- Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

- Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, Benrud-Larson LM, Fealey RD, Vernino S, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: the Mayo clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(3):308-13.

- Shaw BH, Stiles LE, Bourne K, Green EA, Shibao CA, Okamoto LE, et al. The face of postural tachycardia syndrome - insights from a large cross-sectional online community-based survey. J Intern Med. 2019;286(4):438-48.

- Benrud-Larson LM, Dewar MS, Sandroni P, Rummans TA, Haythornthwaite JA, Low PA. Quality of life in patients with postural tachycardia syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(6):531-7.

- Fedorowski A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J Intern Med. 2019;285(4):352-66.

- Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, Shen WK. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20(3):352-8.

- Ganesh R, Bonnes SLR, DiBaise JK. Postural Tachycardia Syndrome: Nutrition Implications. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020;35(5):818-25.

- Benjamin J, Sim L, Owens MT, Schwichtenberg A, Harrison T, Harbeck-Weber C. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Disordered Eating: Clarifying the Overlap. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2021;42(4):291-8.

- Santonicola A, Gagliardi M, Guarino MPL, Siniscalchi M, Ciacci C, Iovino P. Eating Disorders and Gastrointestinal Diseases. Nutrients. 2019;11(12).

- Penny HA, Aziz I, Ferrar M, Atkinson J, Hoggard N, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. Is there a relationship between gluten sensitivity and postural tachycardia syndrome? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(12):1383-7.

- Raj SR, Guzman JC, Harvey P, Richer L, Schondorf R, Seifer C, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement on Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) and Related Disorders of Chronic Orthostatic Intolerance. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(3):357-72.

- Lei LY, Chew DS, Sheldon RS, Raj SR. Evaluating and managing postural tachycardia syndrome. Cleve Clin J Med. 2019;86(5):333-44.

- Eftekhari H. BDLGN, Kavi L., Lobo M.D. In: Postural Tachycardia Syndrome: A Concise and Practical Guide to Management and Associated Conditions. 2021.

- Raj SR. The Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): pathophysiology, diagnosis & management. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2006;6(2):84-99.

- Williams EL, Raj SR, Schondorf R, Shen WK, Wieling W, Claydon VE. Salt supplementation in the management of orthostatic intolerance: Vasovagal syncope and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Auton Neurosci. 2022;237:102906.

- Mittal N, Portera A, Taub P. Improvement of hyperadrenergic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) with methylated B vitamins in the setting of a heterozygous COMT Val158Met polymorphism. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(11).

- Tseng AS, Traub NA, Harris LA, Crowell MD, Hoffman-Snyder CR, Goodman BP, DiBaise JK. Factors Associated With Use of Nonoral Nutrition and Hydration Support in Adult Patients With Postural Tachycardia Syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43(6):734-41.

- Grigoriou E, Boris JR, Dormans JP. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): association with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and orthopaedic considerations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(2):722-8.

- Pederson CL, Brook JB. Health-related quality of life and suicide risk in postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27(2):75-81.