Dietary recommendations designed for the health of both people and planet have become more ‘plant-focused’1 including the EAT Lancet’s Planetary Health Diet2, the UK’s Eatwell Guide (EWG)3, the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations4 and Canada’s Food Guide5.

In fact, the EWG recommends for the population to consume more plant proteins such as beans and pulses alongside animal protein3. In addition, the dairy section of the EWG also highlights the role of unsweetened calcium fortified dairy alternatives as suitable options instead of dairy products. Balanced plant-based diets can provide adequate nutrition for all ages and life stages and are a promising tool for improving the health and well-being of the population, as well as mitigating environmental and climate degradation6.

Who may be interested in consuming plant-based drinks (PBDs)?

With the rise in popularity of plant-based diets, demand for alternatives to dairy has also increased. One in three people in the UK now drink PBDs, rising from 25% in 2020 to 32% in 2021, with further growth predicted7. Derived from a variety of plant sources including grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, PBDs can be used as a replacement for cow’s milk in hot drinks, cereals, smoothies, and in cooking.

A survey in 2022 found that over 25% of people who choose PBDs do so because they enjoy the taste of different options, and around 12% mentioned the ill treatment of cows in the production of dairy products8. In addition, populations more likely to choose dairy alternatives include both children and adults with allergies and intolerances, those seeking improved health outcomes, those who consume a vegan diet, and those with environmental motivations9.

The value of fortified PBDs for those who can't or don't want to have cow's milk

Having a fortified alternative to dairy can be beneficial for a number of population groups, for example those with lactose intolerance which affects on average 65% of the world’s adult population, depending on ethnicity10. Cow’s milk treated with lactase enzyme (to make it lactose free) is another option for those with lactose intolerance.

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is the most common food allergy in young children with an estimated prevalence of 2% of infants and 4.5% of children11,12. For children with CMPA over the age of 1 who are not breastfeeding, fortified PBDs can provide a valuable source of nutrition. For those children with soya allergies (in addition to CMPA) a fortified oat-based drink could provide a valuable source of nutrients especially calcium, iodine, and vitamins D, B12 and B2. The prevalence of soya allergy in those with CMPA ranges from 10-14%13.

Nutritional value

Fortification of foods and drinks can play an important role in ensuring a healthy and balanced diet, especially in some population groups who may struggle to meet the requirements for certain micronutrients14. In Europe, over 90% of PBDs are fortified15.

Calcium and vitamin D

Most fortified PBDs provide a similar quantity of calcium as cow’s milk. Vitamin D is not naturally present in cow’s milk and the addition of vitamin D to PBDs would be expected to further increase the absorption of calcium.

Lower intakes of calcium have been reported in some children and adolescents avoiding dairy products due to CMPA16 or when eating plant-based17 as dairy products are the main source of calcium for most people in the UK. However, there is a misconception that cow’s milk is essential for strong bones and teeth, as it is the calcium that provides the benefit rather than cow’s milk itself18, 19. The addition of calcium to PBDs therefore supports those not including dairy products in their diet to help meet their requirements. Overall, the bioavailability of the calcium added to PBDs is similar to the calcium found in cow’s milk within 10%20.

Very few foods naturally contain vitamin D, with oily fish being the main source and to a lesser extent eggs. Vitamin D aids the absorption of calcium and so the addition of vitamin D to dairy alternatives is helpful.

In the UK, the government recommends a vitamin D supplement of 8.5-10µg per day from birth for all breastfed infants and from 6 months to 4 years of age a supplement of vitamins A and D is recommended for breastfed infants. For formula fed infants, a supplement is only needed when they are drinking less than 500ml of formula per day. For children from the age of 5 years and adults, a vitamin D supplement of 10µg per day is recommended during the autumn and winter months (late September to early April) as we cannot make enough vitamin D in our skin during these months (NHS)21.

Iodine

Iodine is important for thyroid health as it is an essential component of thyroid hormones, needed for many body processes including growth, metabolism and for brain and neurological development of the foetus22. It is therefore very important to ensure an adequate intake of iodine.

In the UK, whilst fish, milk and dairy are rich in iodine, milk is the main dietary iodine source 22,23. Anyone who avoids iodine rich foods could be at risk of iodine deficiency. When avoiding rich sources of iodine, it may be necessary to consider a suitable supplement. There is concern that pregnant women and adolescent girls in the UK are mildly-to-moderately iodine deficient22. According to a UK survey published in 2023, 28% of PBDs were fortified with iodine24. It is therefore advisable to check product labels.

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is made by micro-organisms and is not found in any plant foods unless they are fortified. According to the FEED study (which included intake of PBDs), higher proportions of vegans were below the estimated average requirements (EARs) for vitamin B12 as compared to omnivores25.

Those avoiding all sources of animal foods should take a vitamin B12 supplement or ensure they consume vitamin B12 fortified foods at least twice a day aiming for a minimum of 3mcg per day26. Most dairy alternatives are fortified with vitamin B12 as a way of improving the intake of this important vitamin.

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin)

Dairy products are an important source of vitamin B2, and some studies have shown that those avoiding dairy products can have lower intakes of this vitamin17. This is why vitamin B2 is often added to dairy alternative drinks. Alternative plant-based sources of riboflavin include mushrooms, almonds, and nutritional yeast.

Protein

Soya and pea-based drinks contain the most protein of PBDs, with similar levels to that found in cow’s milk. Oat drinks contain lower levels of protein than that found in cow’s milk, but still contain significant amounts (around 1g per 100ml). Coconut and nut-based drinks contain the lowest amounts of protein (typically around 0.5g or less per 100ml unless they have added protein). PBDs that provide higher levels of protein may be helpful for certain populations (for example older adults or athletes) where protein needs are increased and if not met via other dietary sources27, 28.

It’s important to consider protein contribution from the diet, from food sources such as beans, lentils, nuts, seeds, tofu and other soya foods, foods based on mycoprotein (from fungi) as well as cereals and cereal products which contribute 24% of UK adults (19-64 years) protein intake29. For most people eating a varied and balanced plant-based diet which meets energy needs, protein intake is not a problem with most adults eating more protein than recommended30, 31.

Children’s protein requirements are lower relative to energy needs. For example, the RNI for protein is 14.5g per day for 1–3-year-olds, 19.7g per day for 4–6-year-olds, 28.4g per day for 7–10-year-olds and between 42g and 55g per day depending on age and gender for 11-18 year-olds30. According to NDNS data children are eating well in excess of the amount of protein recommended with 1.5-3-year-olds eating an average of 41g protein per day (283% of the RNI) and 4–10-year-olds an average of 51.9g protein per day31. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found a ‘probable’ causal relationship between a high protein intake (particularly animal sourced protein) in early childhood (less than 18 months of age) and a higher BMI later in childhood32.

Fats

PBDs (except for coconut-based drinks) are rich in unsaturated fats and low in saturated fats, which is a beneficial fat profile in terms of cardiovascular disease risk33, 34, 35. A large cohort study looking at 83,349 women found that replacing 5% of energy from saturated fats with equivalent energy from polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats was associated with estimated reductions in total mortality of 27%33. Most PBDs contain a small amount of either rapeseed or sunflower oil which contain mostly monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Full fat cow’s milk contains just under 4g of total fat per 100ml with 64% being saturated fat.

Carbohydrates and sugars

Carbohydrates are an important source of energy and dietary guidelines recommend that at least 50% of our daily energy intake should come from carbohydrates36. The carbohydrate content of PBDs varies depending on the source, for example, almond/soya/pea-based drinks tend to be lower, whilst oat-based drinks tend to be higher in total carbohydrates, when compared to cow’s milk. The amount of total sugar in PBDs is usually similar (or lower) to that found in cow’s milk. Additionally, there are increasing numbers of PBDs available with no sugars.

Cow's milk does not contain any fibre, whilst PBDs contain varying amounts of fibre with oat-based drinks containing the most.

Nutritional comparison with cow’s milk vs PBDs

The table below shows the average nutritional value per 100ml for a selection of unsweetened and fortified PBDs available in the UK (cow’s milk data from McCance and Widdowson’s Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset 2021)37

|

|

Whole cow’s milk (semi-skimmed) |

Soya-based drinks |

Pea-based drinks |

Oat-based drinks |

Coconut-based drinks |

Almond-based drinks |

|

Energy (kcal) |

63 (46) |

19 - 38 |

24 - 25 |

44 - 59 |

14 - 28 |

13 - 18 |

|

Protein (g) |

3.4 (3.5) |

2.0 - 3.4 |

1.6 - 2.0 |

0.2 - 1.1 |

0.1 - 1.2 |

0.4 - 0.8 |

|

Fat (g) |

3.6 (1.7) |

1.4 - 2.1 |

1.8 - 1.9 |

1.5 - 3 |

1.1 - 2.5 |

1.0 - 1.5 |

|

Carbohydrate (g) |

4.6 (4.7) |

0 - 1.5 |

0.2 - 0.3 |

5.8 - 7.6 |

0 - 3.2**** |

0 - 0.5 |

|

Of which sugars (g) |

4.6 (4.7) |

0 - 0.5 |

0 |

2.8 - 4.2*** |

0 - 0.9 |

0 - 0.5 |

|

Fibre (g) |

0 (0) |

0.5 - 0.6 |

0.1 |

0.7 - 1.9 |

0.2 |

0.3 - 0.5 |

|

Salt (g) |

0.11 (0.11) |

0.08 - 0.14 |

0.1 - 0.13 |

0.1 - 0.13 |

0.1 |

0.15 |

|

Calcium (mg) * |

120 (120) |

120 |

120 - 180 |

104 - 128 |

120 |

120 |

|

Iodine (µg) * |

31 (30)** |

0 - 45 |

0 - 30 |

0 - 36 |

0 - 36 |

35 |

|

Vitamin B12 (µg)* |

0.9 (0.9)***** |

0.38 |

0.38 - 0.9 |

0.24 - 0.9 |

0.38 |

0.38 |

|

Vitamin D (µg)* |

Traces |

0.75 |

0.75 - 1.0 |

0.75 |

0.75 |

0.75 |

|

Vitamin B2 (mg)* |

0.23 (0.24) |

0.21 |

0 |

0 - 0.21 |

0 |

0 - 0.21 |

* level of fortification with vitamins and minerals varies between brands

**iodine in cow’s milk varies depending on the season, higher in winter with values ranging from 20-41µg per 100ml

***a selection of no sugars varieties are now available

**** some coconut drinks have rice flour added which increases the carbohydrate content

*****UHT cow’s milk has lower vitamin B12 levels of 0.2µg per 100ml

Soya drinks - Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Alpro no sugars, Acti leaf, Morrisons, ASDA, M&S

Pea drinks - Sproud, Mighty

Oat drinks - Oatly, Alpro, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, ASDA, Califia

Coconut drinks - Koko, Alpro, Morrisons, ASDA, Aldi

Almond-based drinks - Alpro, ASDA, Sainsbury’s, Almond Breeze

Sustainability credentials

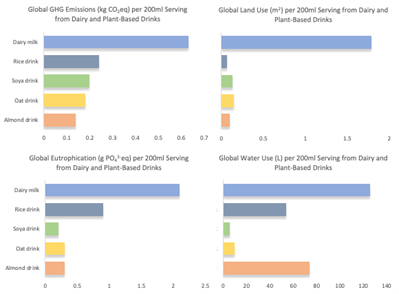

Data shows that switching from cow’s milk to a PBD is a more sustainable option38. According to Oxford University’s global data, as demonstrated in figure 1, some PBDs require up to eighteen times less land area, produce less than a quarter of the greenhouse gases, require a twentieth of the water and produce less than a tenth of the eutrophication effects when compared to cow’s milk39.

Almonds have been criticised for a large water requirement, but with 371 litres of water needed to produce one litre, this remains far less than the global average of 628 litres needed for one litre of cow’s milk. While it has been claimed that UK dairy has improved its ecological footprint, it still ranks lower than plant-based equivalent products on many ecological parameters38, 40.

Figure 1. Global environmental impact of 200ml serving of cow’s milk and PBDs on various environmental parameters38.

Dispelling the myths

Recent media and social media content has been spreading misinformation on PBDs, raising unsubstantiated concerns for the public.

It has been claimed that seed oils, added to improve nutritional profile, mouthfeel, and texture, are ‘toxic’ and cause detrimental inflammation in the body. In reality, seed oils such as rapeseed oil are high in monounsaturated fat and lower in saturated fat, a combination that has been found to reduce levels of LDL-cholesterol41,42, 43 and potentially inflammation44, 45 and the risk of cardiovascular disease46, 47.

Another concern involves the impact of PBDs, particularly oat drinks, on blood sugar levels. As oats are grains, they produce a liquid that is naturally higher in carbohydrates than other PBDs. Despite this, the glycaemic load (which also considers the effect of a normal-sized portion) of oat drink has been categorised as ’low’, meaning that they have a minor effect on blood sugar that is similar to cow’s milk48. It is also important to note that blood sugar effects vary based on individual factors as well as the food matrix of the meal and diet as a whole.

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs), as categorised by the NOVA classification system, are a rising concern in the conversation about healthy diets. Due to processing methods and the addition of nutrients to fortify products, PBDs have been categorised as ‘ultra-processed’. However, there is no evidence linking plant-based drinks to adverse effects seen with UPFs such as processed meat and sweetened soft drinks. This classification system also overlooks the nutrient value of the final product, highlighting issues of using it in isolation to determine health effects49, 50. In fact, the inclusion of some processed food items can provide important nutrients that contribute to a nutritionally adequate diet51.

Plant-based dairy alternatives have an important role in plant-based diets and have a positive impact on human and planetary health. Product development and innovation means that plant-based foods are continuing to adapt to emerging public health needs.

References

- Klapp AL, Feil N, Risius A. A Global Analysis of National Dietary Guidelines on Plant-Based Diets and Substitutions for Animal-Based Foods. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022 Sep 20;6(11):nzac144. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac144. PMID: 36467286; PMCID: PMC9708321. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36467286/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, Garnett T, Tilman D, DeClerck F, Wood A, Jonell M, Clark M, Gordon LJ, Fanzo J, Hawkes C, Zurayk R, Rivera JA, De Vries W, Majele Sibanda L, Afshin A, Chaudhary A, Herrero M, Agustina R, Branca F, Lartey A, Fan S, Crona B, Fox E, Bignet V, Troell M, Lindahl T, Singh S, Cornell SE, Srinath Reddy K, Narain S, Nishtar S, Murray CJL. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019 Feb 2;393(10170):447-492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. Epub 2019 Jan 16. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Feb 9;393(10171):530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30212-0. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Jun 29;393(10191):2590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31428-X. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Feb 1;395(10221):338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30144-6. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Oct 3;396(10256):e56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31828-6. PMID: 30660336. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31788-4/abstract Accessed 14.08.24.

- Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide. Helping you eat a healthy, balanced diet. London: Public Health England, 2016. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/the-eatwell-guide/ Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Nordic Co-operation. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023: Integrating Environmental Aspects. Copenhagen: Nordisk Ministerråd; 2023. Available from: https://www.norden.org/en/publication/nordic-nutrition-recommendations-2023 Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Health Canada. Canada’s dietary guidelines for health professionals and policy makers. 2019. Health Canada, Ottawa, Ont. Available from: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/ Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 Dec;116(12):1970-1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. PMID: 27886704. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27886704/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Mintel. The cream of the vegan milk crop: Sales of oat milk overtake almond in the UK. Sept 21. Available from: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/the-cream-of-the-vegan-milk-crop-sales-of-oat-milk-overtake-almond-in-the-uk/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Statista Search Department. Which, if any, of the following best describes why you include plant-based milk in your diet nowadays? [chart] Nov 22. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1388209/consumers-reasons-for-drinking-plant-based-milk-in-the-united-kingdom/#statisticContainer Accessed 21.07.24.

- Statista Search Department. Which, if any, of the following best describes why you include plant-based milk in your diet nowadays? [chart] Nov 22. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1388209/consumers-reasons-for-drinking-plant-based-milk-in-the-united-kingdom/ Accessed 05.08.24.

- Malik TF, Panuganti KK. Lactose Intolerance. [Updated 2023 Apr 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532285/ Accessed 29.08.24.

- World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow's Milk Allergy (DRACMA) guidelines update – XVI - Nutritional management of cow's milk allergy. Venter, Carina Ansotegui, Ignacio et al. World Allergy Organization Journal, Volume 17, Issue 8, 100931 Accessed 29.08.24.

- Flom JD, Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of Cow's Milk Allergy. Nutrients. 2019 May 10;11(5):1051. doi: 10.3390/nu11051051. PMID: 31083388; PMCID: PMC6566637. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31083388/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Kattan JD, Cocco RR, Järvinen KM. Milk and soy allergy. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011 Apr;58(2):407-26, x. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.02.005. PMID: 21453810; PMCID: PMC3070118. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21453810/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- The British Dietetic Association (BDA). Policy Statement Food Fortification. 2021 Jan. Available from: https://www.bda.uk.com/uploads/assets/07017d3c-05f4-4254-902c1649343d3a95/Food-Fortification-Policy-Statement-FINAL-Approved.pdf Accessed 14.08.24.

- Röös E, Garnett T, Watz V, Sjörs C. The role of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives in sustainable diets. SLU Future Food Reports 3. 2018 Dec. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala. Food Climate Research Network (FCRN), London. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330506721_The_role_of_dairy_and_plant_based_dairy_alternatives_in_sustainable_diets Accessed 14.08.24.

- Mailhot G, Perrone V, Alos N, Dubois J, Delvin E, Paradis L, Des Roches A. Cow's Milk Allergy and Bone Mineral Density in Prepubertal Children. Pediatrics. 2016 May;137(5):e20151742. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1742. PMID: 27244780. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27244780/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Alexy U, Fischer M, Weder S, Längler A, Michalsen A, Sputtek A, Keller M. Nutrient Intake and Status of German Children and Adolescents Consuming Vegetarian, Vegan or Omnivore Diets: Results of the VeChi Youth Study. Nutrients. 2021 May 18;13(5):1707. doi: 10.3390/nu13051707. PMID: 34069944; PMCID: PMC8157583. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34069944/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Cormick G, Betran AP, Romero IB, Cormick MS, Belizán JM, Bardach A, Ciapponi A. Effect of Calcium Fortified Foods on Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 22;13(2):316. doi: 10.3390/nu13020316. PMID: 33499250; PMCID: PMC7911363. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33499250/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, Kalkwarf HJ, Lappe JM, Lewis R, O'Karma M, Wallace TC, Zemel BS. The National Osteoporosis Foundation's position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int. 2016 Apr;27(4):1281-1386. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3440-3. Epub 2016 Feb 8. Erratum in: Osteoporos Int. 2016 Apr;27(4):1387. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3551-5. PMID: 26856587; PMCID: PMC4791473. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26856587/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Rafferty K, Walters G, Heaney RP. Calcium fortificants: overview and strategies for improving calcium nutriture of the U.S. population. J Food Sci. 2007 Nov;72(9):R152-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00521.x. PMID: 18034744. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18034744/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- NHS. Vitamins and minerals. Vitamin D. 2020 August. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vitamins-and-minerals/vitamin-d/ Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Bath SC, Hill S, Infante HG, Elghul S, Nezianya CJ, Rayman MP. Iodine concentration of milk-alternative drinks available in the UK in comparison with cows' milk. Br J Nutr. 2017 Oct;118(7):525-532. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517002136. Epub 2017 Sep 26. PMID: 28946925; PMCID: PMC5650045. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28946925/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Dineva M, Rayman MP, Bath SC. Iodine status of consumers of milk-alternative drinks v. cows' milk: data from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Br J Nutr. 2021 Jul 14;126(1):28-36. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520003876. Epub 2020 Sep 30. PMID: 32993817. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32993817/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Nicol K, Thomas EL, Nugent AP, Woodside JV, Hart KH, Bath SC. Iodine fortification of plant-based dairy and fish alternatives: the effect of substitution on iodine intake based on a market survey in the UK. Br J Nutr. 2023 Mar 14;129(5):832-842.

- Lawson I, Wood C, Syam N, Rippin H, Dagless S, Wickramasinghe K, Amoutzopoulos B, Steer T, Key TJ, Papier K. Assessing Performance of Contemporary Plant-Based Diets against the UK Dietary Guidelines: Findings from the Feeding the Future (FEED) Study. Nutrients. 2024 Apr 29;16(9):1336. doi: 10.3390/nu16091336. PMID: 38732583; PMCID: PMC11085280. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38732583/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- The Vegan Society. Vitamin B12. Available from: https://www.vegansociety.com/resources/nutrition-and-health/nutrients/vitamin-b12 Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Baum JI, Kim IY, Wolfe RR. Protein Consumption and the Elderly: What Is the Optimal Level of Intake? Nutrients. 2016 Jun 8;8(6):359. doi: 10.3390/nu8060359. PMID: 27338461; PMCID: PMC4924200. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27338461/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Campbell B, Kreider RB, Ziegenfuss T, La Bounty P, Roberts M, Burke D, Landis J, Lopez H, Antonio J. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2007 Sep 26;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-4-8. PMID: 17908291; PMCID: PMC2117006. Available from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17908291/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS): results from years 9 to 11 (2016 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019) data tables. Percentage contribution of food groups to average daily protein intake. 2020. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019 Accessed 15.08.2024.

- Public Health England. Government Dietary Recommendations. 2016. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a749fece5274a44083b82d8/government_dietary_recommendations.pdf Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS): results from years 9 to 11 (2016 to 2017 and 2018 to 2019). 2020. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/ndns-results-from-years-9-to-11-2016-to-2017-and-2018-to-2019 Accessed 13.08.2024.

- Arnesen EK, Thorisdottir B, Lamberg-Allardt C, Bärebring L, Nwaru B, Dierkes J, Ramel A, Åkesson A. Protein intake in children and growth and risk of overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Nutr Res. 2022 Feb 21;66. doi: 10.29219/fnr.v66.8242. PMID: 35261578; PMCID: PMC8861858. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35261578/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Wang DD, Li Y, Chiuve SE, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Association of Specific Dietary Fats With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Aug 1;176(8):1134-45. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2417. PMID: 27379574; PMCID: PMC5123772. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27379574/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Zhuang P, Zhang Y, He W, Chen X, Chen J, He L, Mao L, Wu F, Jiao J. Dietary Fats in Relation to Total and Cause-Specific Mortality in a Prospective Cohort of 521 120 Individuals With 16 Years of Follow-Up. Circ Res. 2019 Mar;124(5):757-768. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314038. PMID: 30636521. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30636521/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Naghshi S, Aune D, Beyene J, Mobarak S, Asadi M, Sadeghi O. Dietary intake and biomarkers of alpha linolenic acid and risk of all cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2021 Oct 13;375:n2213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2213. PMID: 34645650; PMCID: PMC8513503. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34645650/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (NDA); Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA Journal 2010; 8(3):1462 [77 pp.]. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1462. Available from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1462 Accessed 11.09.2024

- McCance and Widdowson's The Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset 2021. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/composition-of-foods-integrated-dataset-cofid Accessed 15.08.2024

- Carlsson Kanyama A, Hedin B, Katzeff C. Differences in Environmental Impact between Plant-Based Alternatives to Dairy and Dairy Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12599. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212599 https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/22/12599 Accessed 14.08.24.

- Poore J, Nemecek T. Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 2018 Jun 1;360(6392):987-992. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0216. Erratum in: Science. 2019 Feb 22;363(6429):eaaw9908. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw9908. PMID: 29853680. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29853680/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Scheelbeek P, Green R, Papier K, et al. Health impacts and environmental footprints of diets that meet the Eatwell Guide recommendations: analyses of multiple UK studies. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e037554.DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037554 Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/8/e037554 Accessed 14.08.24.

- Schoeneck M, Iggman D. The effects of foods on LDL cholesterol levels: A systematic review of the accumulated evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021 May 6;31(5):1325-1338. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33762150/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Schwingshackl L, Bogensberger B, Benčič A, Knüppel S, Boeing H, Hoffmann G. Effects of oils and solid fats on blood lipids: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Lipid Res. 2018 Sep;59(9):1771-1782. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P085522. Epub 2018 Jul 13. PMID: 30006369; PMCID: PMC6121943. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30006369/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Ghobadi S, Hassanzadeh-Rostami Z, Mohammadian F, Zare M, Faghih S. Effects of Canola Oil Consumption on Lipid Profile: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2019 Feb;38(2):185-196. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2018.1475270. Epub 2018 Oct 31. PMID: 30381009. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30381009/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Kruse M, von Loeffelholz C, Hoffmann D, Pohlmann A, Seltmann AC, Osterhoff M, Hornemann S, Pivovarova O, Rohn S, Jahreis G, Pfeiffer AF. Dietary rapeseed/canola-oil supplementation reduces serum lipids and liver enzymes and alters postprandial inflammatory responses in adipose tissue compared to olive-oil supplementation in obese men. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015 Mar;59(3):507-19. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400446. Epub 2014 Dec 22. PMID: 25403327. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25403327/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Kaluza J, Harris H, Melhus H, Michaëlsson K, Wolk A. Questionnaire-Based Anti-Inflammatory Diet Index as a Predictor of Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018 Jan 1;28(1):78-84. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7330. Epub 2017 Oct 12. PMID: 28877589. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28877589/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JHY, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV; American Heart Association. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Jul 18;136(3):e1-e23. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. Epub 2017 Jun 15. Erratum in: Circulation. 2017 Sep 5;136(10):e195. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000529. PMID: 28620111. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28620111/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Zhuang P, Zhang Y, He W, Chen X, Chen J, He L, Mao L, Wu F, Jiao J. Dietary Fats in Relation to Total and Cause-Specific Mortality in a Prospective Cohort of 521 120 Individuals With 16 Years of Follow-Up. Circ Res. 2019 Mar;124(5):757-768. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314038. PMID: 30636521. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30636521/

- Oatly. Is Oatly Oat Drink Like Soda? 2022. Accessed 05.08.2024. Available from: https://community.oatly.com/conversations/news-and-views/is-oatly-oat-drink-like-soda/6319a8f9eb08200ed8a11fbf Accessed 14.08.24.

- Astrup A, Monteiro CA. Does the concept of "ultra-processed foods" help inform dietary guidelines, beyond conventional classification systems? NO. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022 Dec 19;116(6):1482-1488. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac123. PMID: 35670128. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35670128/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Gibney MJ, Forde CG. Nutrition research challenges for processed food and health. Nat Food. 2022 Feb;3(2):104-109. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00457-9. Epub 2022 Feb 7. PMID: 37117956. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37117956/ Accessed 14.08.24.

- Hallinan S, Rose C, Buszkiewicz J, Drewnowski A. Some Ultra-Processed Foods Are Needed for Nutrient Adequate Diets: Linear Programming Analyses of the Seattle Obesity Study. Nutrients. 2021 Oct 28;13(11):3838. doi: 10.3390/nu13113838. PMID: 34836094; PMCID: PMC8619544. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34836094/ Accessed 14.08.24.